From online hacks to plastic fakes: The strange life of a stolen credit card - By Keith Wagstaff NBC News

Six days before Christmas, Shaw Lash's debit card was used at a Toys R Us in the New York City borough of Brooklyn.

The problem? Lash wasn't at Toys R Us buying gifts. In fact, she had her card with her when Chase Bank sent her a text message warning that someone had just tried to make a suspicious purchase for $379 using her account numbers.

"It was kind of sad," Lash, 33, a video producer from Manhattan, told NBC News, noting the holiday timing. She had, however, been shopping at a Target in Vauxhall, N.J., during the first week of December. That convinced her that she was one of the up to 40 million Target customers who had their credit or debit card information stolen between Nov. 27 and Dec. 15 from retail stores throughout the United States.

Like other bank customers, she wasn't told exactly where her debit card data had been stolen from, so the timing could just be a coincidence. Still, that doesn't change the fact that someone with a fake version of her debit card nearly got away with boosting some Christmas loot until the purchase was rejected at the register.

"The thing about it that makes me uncomfortable is that you don't use credit cards online at vendors that aren't reputable," Lash told NBC News. "You want to use Amazon, or go to Barnes & Noble or Target because they give you a sense of security and safety."

So, how did a fake debit card with Lash's number end up in someone's else hands? Here is what usually happens when your financial information is hijacked by hackers.

How do credit and debit card numbers get stolen?

Here is what we do know about the Target hack: The company's point-of-sale (POS) system was infected with malware, the company confirmed earlier this week. That means instead of being stolen from a database, information was sent directly from Target's physical checkout system to the criminals — a breach some experts are calling unprecedented for its combined size and sophistication.

If there is a weakness in a system, opportunistic hackers will find it. In 2007, criminals exploited the lax Wi-Fi security used with hand-held price-checking devices at multiple Marshalls locations. That resulted in 45.7 million credit card numbers being stolen from the store's parent company, TJX.

Criminal outfits also go after third-party payment processors, like Heartland Payment Systems, which suffered a massive breach in 2009 when SQL injection attacks (a common technique used by hackers) resulted in 130 million exposed card numbers.

Who is buying this stuff?

Massive breaches are usually the work of large, organized outfits spread across multiple countries. In July, five men were indicted in connection with the Heartland Payment Systems attack — four were located in Russia, with the other based in the Ukraine.

The masterminds, however, usually aren't the ones who end up in jail.

"The people who steal passwords are smart enough and risk-averse enough not to use them," Chester Wisniewski, senior security adviser at Sophos, told NBC News. "They might lose 60 to 70 percent of their take through the laundering process, but they don't care, because it's not their money."

Below them are usually four or more levels of criminal "employees." Those include re-sellers who buy and sell the card numbers in online "carding forums," people who print fake cards to use in stores, recruiters who find people to buy goods with those fake cards, and those on the lowest rung that actually make the purchases.

How much do credit card numbers sell for?

It varies wildly depending on the quality of the information stolen. You can score 10,000 bottom-of-the-barrel cards — which could include canceled and other high-risk cards — for as little as $10 or $20 total.

On the other end of the spectrum, a single card stolen from the Target breach was reportedly selling for as much $135, according to security researcher Brian Krebs, partly because it was issued by a foreign bank. (Foreign institutions might not be as vigilant about the Target hack as JP Morgan Chase and other American banks, making their cards less likely to get canceled, Wisniewski said).

Just by looking at the first six numbers of a stolen credit card, online buyers can tell the difference between a regular Visa card and a more valuable platinum American Express card. Added information, like zip codes and three-digit card verification value (CVV) codes, make cards worth even more.

And while thieves might prefer online shopping for the anonymity, they can put magnetic stripes on fake credit cards with equipment that costs as little as $100, according to Dave Lott, retail payments risk expert at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Often, the number stored on the stripe doesn't match the number on the generic, mass-produced card because creating individualized fakes is too expensive. That is why some retailers enter the last four digits of each physical card into the register after swiping — if the numbers don't match, it's a fake.

What are the bad guys buying?

Pretty much anything. But the most common scheme involves a recruiter getting people to buy products with high resale values, like Apple products, and then selling them on sites like eBay or Craigslist, Wisniewski said.

Recruiters work by sending out spam. Ever get an email promising that you could make $3,000 a month by working from home? There is a decent chance that it was from a recruiter looking for people to buy stuff with stolen credit card numbers in exchange for cash. Sometimes, to cover their tracks, recruiters will insist on using gift cards or prepaid debit cards to make the final purchase.

And yes, the people on the bottom of the totem pole are often the ones who have to assume most of the risk and ship the ill-gotten goods to the consumer, while the recruiters keep the profits.

Isn't all of this risky?

Multiple security experts claimed that it's incredibly difficult to take down these shadowy, international organizations. But that doesn't mean dealing in fake cards is risk-free.

Criminal outfits always have to be on the lookout for law enforcement agents posing as interested buyers. In 2010, the FBI even started its own carding forum, Carder Profit, and tracked criminals as they bought and sold stolen credit card numbers. The undercover operation resulted in 24 arrests.

Even private chats aren't safe. Suspects in the Heartland Payment Systems hack reportedly moved from communicating via normal chat to encrypted chat to face-to-face meetings after they feared they were being watched by investigators. They were right.

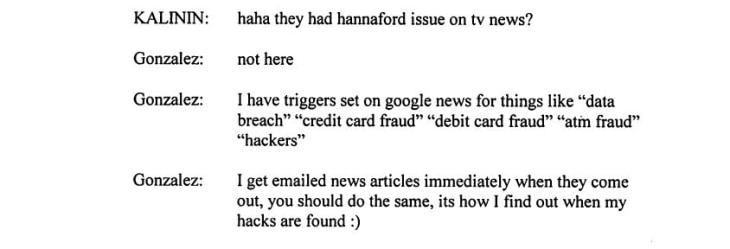

Here is sample of a conversation, taken from court records, between suspect Aleksander Kalinin of St. Petersburg, Russia, and Albert Gonzalez, of Miami, Fla. (Gonzalez is currently serving a 20-year prison sentence on multiple charges relating to hacking and credit card fraud, including a case involving the Hannaford Brothers supermarket chain.)

Department of Justice

Bragging online isn't the only risk they take. Moving money around is also a big problem, especially with authorities working with money transfer companies like Western Union and MoneyGram.

"When one crook is from Lithuania, another is in Russia and one is from Nebraska, it becomes a very difficult problem, because PayPal doesn't want your business," Wisniewski said. "It's like any other crime. Follow the money."

As for Lash, she still plans to use her cards as usual, despite being the victim of a virtual heist.

"I have had information stolen in the past," she said. "It's not just Target. I think we're just less secure in general. I'm just glad for banks erring on the side of caution.

Keith Wagstaff writes about technology for NBC News. He previously covered technology for TIME's Techland and wrote about politics as a staff writer at TheWeek.com. You can follow him on Twitter at @kwagstaff and reach him by email at: Keith.Wagstaff@nbcuni.com